It’s a little late for Christmas stories, but nevertheless, please enjoy this piece about what it was like to celebrate Christmas for those on the Corps of Discovery. This article was originally published in the December issue of American Heartland Magazine, so if you enjoy it, head on over to americanheartlandmagazine.com to check out other winter tales!

The longing for discovery has driven mankind on the most extraordinary, daunting, and perilous adventures the planet has ever known. It has propelled us beyond oceans, carried us to the top of the world, thrust us beyond our own atmosphere. It was, in no uncertain terms, what sent over forty men up the Missouri River into the Louisiana Territory—a fresh addition to the young United States in 1804. This Corps of Discovery, as it was named, was tasked with documenting the newly acquired land: its terrain, plants, animals, people, and general goings-on (among much else).

The leaders of this expedition, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, spent about two and a half years out in the untamed heart of America with their men. Of course, folks know the broad strokes of this famed odyssey—Sacagawea, grizzly encounters, unspoiled landscapes, that sort of stuff—but what might get overlooked are the more mundane aspects of their existence in terra incognita. For instance, the captains and their men spent three Christmases together on the frontier, two of which were celebrated right here in the Heartland. And this is how they spent them.

Camp Dubois, 1803

In the winter of 1803, Clark established Camp Dubois—a small, rough-hewn wooden fortress that would see the Corps through the bitter Illinois winter. Today, the exact location of the encampment cannot be pinpointed due to shifts in the Missouri and Mississippi rivers over the last 220 years; however, we do know it sat at the confluence of the two rivers, on the eastern side of the Mississippi. But why the eastern side? Well, the Louisiana Territory (west of the river) was not yet American property at that time. The US wouldn’t officially acquire the nearly one million square miles until March the following year.

So while Clark was busy recruiting men, training them, and overseeing the construction and maintenance of their small winter fortress, Lewis was off across the river in the bustling frontier town of St. Louis. There, he gathered maps and intelligence about the Upper Missouri region, purchased provisions and gifts, and sent dispatches to President Jefferson. He also played a crucial role in documenting the transfer of the Louisiana Territory from France to the US and in fostering good relations with the Spanish authorities in St. Louis. Neither Lewis nor Clark was leading a particularly glamorous life at the time, but they were serving two disparate yet essential roles in preparing the expedition to head upriver the following spring.

That first Christmas in the Corps was not opulently celebrated, though it was celebrated all the same. Lewis was still across the river, so not much is known about how he spent the holiday, but over at the still-unfinished Camp Dubois, Clark awoke to a celebratory volley of gunfire at daybreak. After rising and no doubt steeling himself to face the biting dawn air, he left his “hut” to discover a monochromatic landscape—fresh snow veiled the ground as frozen crystals glided down from the sky. What might well have been a perfectly serene Christmas morning was soured by an unfortunate discovery, however. Clark found that some of the men had already taken to drinking, and two had already brawled. Given that the expedition was a military operation, it seems surprising that Clark made no mention of what punishment these men faced—if any at all. Months later, in June 1804, two men (Hall and Collins) were court-martialed for stealing whiskey and drunkenness, respectively. Hall got off easier with just 50 lashes; Collins got 100, well laid on. Perhaps, then, Clark was feeling festive and compassionate that wintry morning, allowing the drunken combatants to get off scot-free. Maybe that was their Christmas gift; we’ll never know.

The remainder of Christmas day at Camp Dubois was spent frolicking—celebrating, dancing, singing—and hunting, which resulted in several turkeys getting bagged. One man, John Shields, returned to camp with four pounds of butter and some cheese (where he got these is not mentioned in Clark’s journal). Sometime later, three Indians stopped by to “take Christmas with us,” according to Clark, who gave them a bottle of whiskey. Clark’s last entry for that jolly day noted that a man named George Drouillard had agreed to join the party. Drouillard, or Drewyear as Clark spelled it, was one of the few civilians in the Corps of Discovery and would go on to become one of Lewis and Clark’s most trusted and vital men on the expedition. He proved to be an expert hunter, scout, adviser, and interpreter—having a Shawnee mother and French-Canadian father, he was fluent in French, English, two Native languages, and the sign language of the Plains Indians.

All in all, it seemed to be a very merry and gainful Christmas at Camp Dubois in 1803.

Fort Mandan, 1804

As spring descended and the ice melted, the Corps of Discovery grew increasingly eager to embark on its monumental expedition. During the days, the men packed, unpacked, and repacked the boats as Clark experimented with different configurations. At night, they too often got drunk and incurred the displeasure of their captain. But Clark knew this sort of errant behavior would subside once they were on the move. And on May 14, the Corps finally shoved off from Camp Dubois and started up the Missouri. Meeting Lewis at St. Charles, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was finally fully stocked, fully manned, and on its way.

Originally, President Jefferson authorized a party of 12-15 men for the journey—but Lewis quickly realized they’d need far more. By the time the expedition headed up the Missouri River, it had tripled in size. Forty-five members, including Clark’s slave York and Lewis’ dog Seaman, now trudged their way west (though 16 would be sent back downriver later). But even with all that manpower, the journey was arduous at best—hopeless at worst. They battled heat, insects, injuries, and the river itself, averaging just 15 miles a day. By October 1804, they reached the Mandan and Hidatsa villages near present-day Washburn, North Dakota, where they’d build a fort and wait out the brutally cold winter closing in.

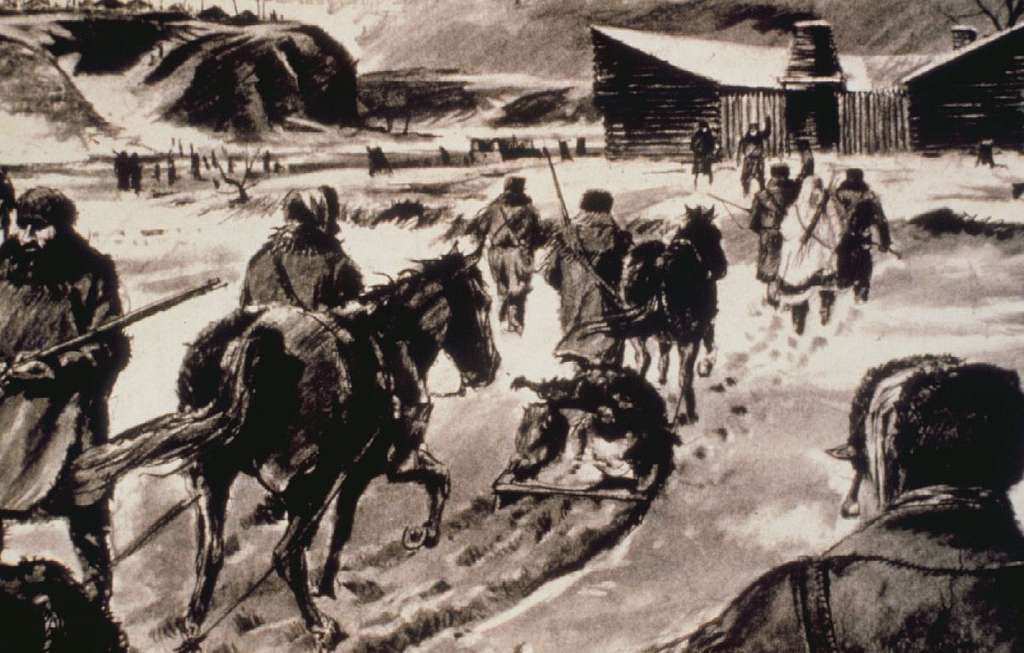

On Christmas Eve morning, snow dusted everything as the men put the finishing touches on Fort Mandan—erecting the last of the pickets and setting up a blacksmith shop in an empty room. Later that evening, “Flour, dried apples, pepper and other articles” were distributed in preparation for Christmas Day so the men could celebrate “in a proper and social manner.”

As the sun rose on Christmas morning at the fort, a downy snow once again descended from above. The temperature sat at a glacial 15 degrees. And despite this, the men were already “merrily Disposed” by that time, waking the captains with a salute of rifle fire at first light. To usher in the day, two shots rang out from the boat-mounted swivel gun, followed by another volley from every man in the fort. Clark then poured a glass of Taffia for each man—rum mixed with water—to kick off the Christmas Day drinking (a tradition I, too, partake in, though with champagne instead). Sometime thereafter, the American flag was hoisted and flown over the fort for the first time, so the captains permitted three shots to be fired from the cannon, and each man received another round of refreshments.

After a boozy (and undoubtedly smoky) Christmas morning, the men cleared out a room in the fort to make space for dancing; others, according to Clark, headed out to hunt. The celebrations at Fort Mandan were far livelier than those back at Camp Dubois a year earlier. By all accounts, the day was filled with dancing, and eating, and drinking. Violins provided the music, and a cannon shot announced when meals were ready. Then it was right back to dancing again. Seemingly, the only ones not dancing were the interpreters’ wives, one of whom was a young mother named Sacagawea, “who took no other part than the amusement of looking on.” The revelry continued until 9 PM, when the party finally wound down. According to Clark, that night was peaceful and quiet—hardly surprising after nearly fourteen hours of festivities.

Christmas is Still Christmas

Detailed as the Lewis and Clark journals are, they still leave much to the imagination. What conversations were had? Were they optimistic? Did they worry about what was to come? Maybe the men waxed longingly about their loved ones, or nattered imperturbably about what they’d seen thus far. Certainly, they must have remarked on the magnitude of what they were engaged in. But through the journals’ pages, one thing is undeniably clear: the holiday celebrations were much as they are now. They were full of drinking, music, laughter. It seems that whether you are besieged by the unknown or bathed in the hearth’s warm glow, Christmas is still Christmas.

Leave a comment